[ad_1]

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates (AP) — When U.N. climate talks wrap up in Dubai some point this week, big promises will be made about how the world will tackle climate change caused by the burning of fossil fuels like oil. , gas and coal.

Negotiators are debating how fast fossil fuels should be phased out and how to pay for a major shift to green energy, raising the prospect of a historic deal.

Previous summits have ended with funds established to help developing countries transition to green energy, pledges to reduce pollution and promises to put the most vulnerable people at the center of policy discussions.

But are the countries adamant on their point?

Before whatever decisions come from this year’s talks, here’s a look at five big promises from nearly 30 years of negotiations, and what’s happened since.

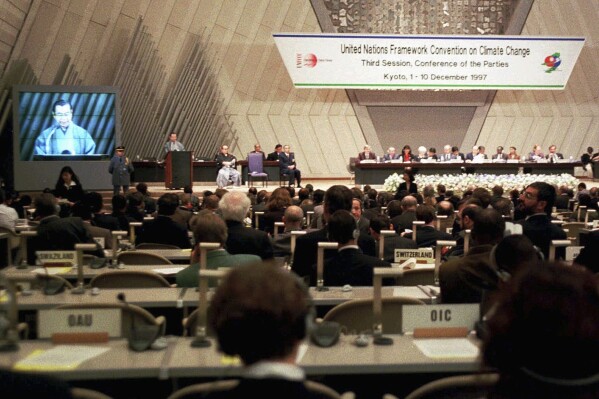

emission reduction in kyoto

The third climate summit took place in Kyoto, Japan in 1997 – one of the hottest years recorded in the 20th century.

Known as the Kyoto Protocol, the agreement called for 41 high-emitting countries around the world and the European Union to cut their emissions by a little more than 5% compared to 1990 levels. Cutting emissions can come from a number of places, from deploying green energy like wind and solar that doesn’t produce emissions to making things that make combustion-engined vehicles run more cleanly.

Despite agreements on emissions reductions, it was only in 2005 that countries finally agreed to act on the Kyoto Protocol. The United States and China – the two largest emitters then and now – did not sign the agreement.

Kyoto was not successful in keeping the promises made. Emissions have increased dramatically since then. At the time, 1997 was the hottest year on record since the pre-industrial period. 1998 broke that record, and more than a dozen years have passed since then.

But Kyoto is still considered a landmark moment in the fight against climate change because it was the first time that so many countries recognized the problem and pledged to act on it.

Copenhagen’s climate cash

By the time the 2009 conference in Denmark approached, the world was ending its hottest decade on record – that is. since broken,

The summit is widely regarded as a failure in the impasse between developed and developing countries over emissions cuts and whether poor countries can use fossil fuels to boost their economies. Still, it saw one key pledge: money for countries to transition to clean energy.

Rich countries pledged to provide $100 billion per year to developing countries for green technologies by 2020. But they failed to reach $100 billion as of early 2020, drawing criticism from developing states and environmentalists alike.

In 2022, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development said rich countries could eventually meet and exceed the $100 billion target. But Oxfam, a group that focuses on anti-poverty efforts, said it was likely that 70% of the money was in the form of loans, which actually increased the debt crisis in developing countries.

And as climate change worsens, experts say the promised money is not enough. Research published by climate economist Nicholas Stern found that developing countries will need $2 trillion each year for climate action by 2030.

French President Francois Hollande, right, French Foreign Minister and COP21 President Laurent Fabius, second right, UN climate chief Christiana Figueres, left, and UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon raise their hands in celebration after the final summit . COP21, the United Nations conference on climate change, in Le Bourget, north of Paris, on December 12, 2015. (AP Photo/Francois Mori)

paris agreement

It was not until 2015 that a global agreement to fight climate change was adopted by nearly 200 countries, calling on the world to collectively reduce greenhouse gases. But they decided that it would be non-binding, so countries that did not comply would not be subject to sanctions.

The Paris Agreement is widely considered the United Nations’ greatest achievement in efforts to combat climate change. Exactly eight years ago, on December 12, this was agreed upon in a standing ovation in the plenary session. Nations agreed to keep temperatures “well below” 2 °C (3.8 °F) above pre-industrial times, and ideally no more than 1.5 °C (2.7 °F).

The legacy of Paris continues, with the goal of limiting temperature rise to 1.5 degrees still central to climate discussions. Scientists agree that the 1.5 limit needs to be maintained because every tenth degree of warming brings even more devastating consequences in the form of extreme weather events to an already hot planet. The world has not yet exceeded the limits set in the Paris Agreement – it has warmed around 1.1 or 1.2 °C (2 to 2.2 °F) since the early 1800s – but it is currently on its way, as long as That drastic reductions in emissions are not achieved quickly.

Glasgow and coal

Six years after Paris, global warming had reached such a critical point that negotiators were looking to renegotiate the goal of limiting warming to agreed levels in 2015.

The average temperature was already 1.1 °C (1.9 °F) higher than in pre-industrial times.

The Glasgow summit was postponed to 2021 as the world was emerging from the COVID-19 pandemic. This included mass protests led by climate activist Greta Thunberg, who helped lead a global movement of youth activists to demand more action from leaders.

After last-minute disagreements over the language of the final document, the countries agreed to a “phase out” of coal, which was less strong than the original idea of ”phasing out”. India and China, two highly coal-dependent emerging economies, pushed for weakening the language.

Burning coal produces more emissions than any other fossil fuel, accounting for about 40% of global carbon dioxide emissions. Burning of oil and gas is also a major source of emissions.

So far, countries have failed to meet the Glasgow deal. Emissions from coal have increased slightly and major coal-using countries have not yet begun to move away from the dirtiest fossil fuel.

India is an example of this. It relies on coal for more than 70% of its electricity generation, and plans a major expansion of coal-fired power generation capacity over the next 16 months.

Loss and damage in Sharm el-Sheikh

At climate talks last year in the Egyptian resort city of Sharm el-Sheikh, countries agreed for the first time to create a fund to help poor countries recover from the impacts of climate change.

A few months after devastating floods in Pakistan, which killed nearly 2,000 people and caused more than $3.2 trillion in damage, COP27 delegates decided to establish a Loss and Damage Fund to compensate for destroyed homes, flooded lands and land damaged by climate change. Income from crops can be reduced. Gave compensation.

The fund was formally created on the first day of this year’s talks in Dubai, after disagreements over what the fund should look like. More than $700 million has already been pledged. The pledges – and the amounts that countries choose to commit – are voluntary.

Climate experts say the pledges are a small part of the billions of dollars needed, as climate-driven weather extremes such as cyclones, rising sea levels, floods and droughts are increasing as temperatures rise. ,

Editor’s note: This article is part of a series produced under the India Climate Journalism Program, a collaboration between the Associated Press, the Stanley Center for Peace and Security and the Press Trust of India.

,

Associated Press climate and environmental coverage receives support from several private foundations. See more about AP’s climate initiative Here, AP is solely responsible for all content.

[ad_2]

Source link