[ad_1]

Alyssa Reyes has been coming to Plaza del Sol Family Health Center for doctor’s appointments for more than a decade. Although she moved away some time ago, the 33-year-old keeps coming back, even if it means taking a two-hour roundtrip bus ride.

This is because both of her children see the same doctor that she sees. Because when she is sick, she can walk in without an appointment. Because Queens Clinic staff helped her apply for health insurance and food stamps.

“I feel like home. They even speak my language,” Reyes said in Spanish. “I feel comfortable.”

Plaza del Sol is one of two dozen sites operated by Urban Health Plan Inc., one of about 1,400 federally designated community health centers. One in 11 Americans depends on them to get routine medical care, social services and, in some cases, fresh food.

Clinics serve as a vital safety net for low-income people of all ages in every state and U.S. territory. But it is a safety net under stress.

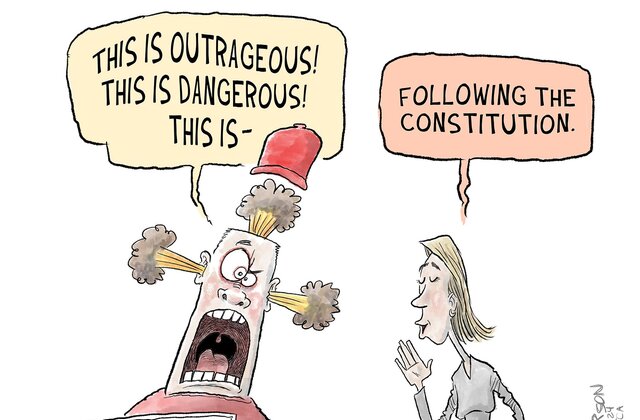

political cartoon

Since 2012, community health centers have seen a 45% increase in the number of people seeking care – and they’ve opened more service sites to expand their footprint to more than 15,000 locations.

Many centers are understaffed and struggling to compete for doctors, mental health professionals, nurses and dentists. Leaders also told The Associated Press that funding is an ongoing concern, even as months go by. debate on the federal budget Which has made it almost impossible for them to plan and make appointments for the long term.

Despite this, centers are trying to improve their communities’ health and access to primary care by looking at disparities that begin before a patient even steps into the exam room.

Community health centers, in one form or another, have existed for decades, and they continue to serve a community at large when urban and rural hospitals shut down or cut back,

Dr. Matthew Kusher, clinical director of Plaza del Sol, said there are things prescriptions can’t change, like preventing the spread of flu and COVID-19 when people live in apartments with one family per room. And it is impossible to quarantine.

“What we provide here is only 20% of what it costs to spend on someone’s health,” Kusher said. “Their health is more driven by other factors, more driven by poverty, and lack of access to food or clean water or healthy air.”

According to the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration, nine out of 10 health center patients live at or below 200% of the federal poverty line. Beyond that:

– In 2022, approximately 1.4 million health center patients were homeless.

– One in five was not insured.

– Half the people were on Medicaid.

– One in four were best served in a language other than English; About 63% were racial or ethnic minorities.

“We continue to confront these disparities head-on in the communities that need it most,” said Dr. Ky Rhee, president of the National Association of Community Health Centers. “We have a workforce that works tirelessly, diligently and is flexible and diverse – representing the people they serve. And that trust is very important.”

Yelisa Sierra, specialty case manager at Plaza del Sol, said she often fields questions about people in need of clothing, food or shelter. Recently, the clinic serves many newcomers migrants, She wishes she had a better answer to the question she hears most: Where can they find work?

“It’s not just a medical need, it’s a feeling,” said Sierra, sitting in a cramped office near a crowded waiting room. “They need someone who will listen to them. Sometimes, it’s just that.”

Fifty years ago, Dr. Aqlema Mohammed started as a medical assistant at the urban health plan’s first clinic, the San Juan Health Center. They have taken care of some families for three generations.

“Working in this community is very gratifying. I walk through the door, or I walk down the street, and I get hugs,” she said. “Always, ‘Oh Dr. Mo!’ You’re still here!'”

Mohammed’s biggest concern is staffing. Many pediatricians retired or moved on to other jobs after the worst of the pandemic. It’s not just about the money, either: He said job applicants tell him they want quality of life and flexibility, no weekends or long hours.

“It’s a big job and it’s a big issue because we have a lot of sick kids and a lot of sick patients, but we don’t have enough providers to take care of them,” Mohammed said.

Former pediatricians are sometimes doing virtual visits to provide respite, she said, and telehealth also helps.

When patients can’t make telehealth, El Nuevo San Juan Health Center tries to take care of them. Dr. Manuel Vazquez, vice president of medical affairs for the urban health plan, who oversees the home health program, said about 150 elders are visited at home.

There are times when home visits are not covered, but the team does so nonetheless, without receiving payment.

“We said, ‘No. We need to do this,'” he said.

One of the nation’s first community health centers opened in the rural Mississippi Delta in 1967 in the wake of the Civil Rights Movement’s Freedom Summer.

Delta Health Centers in Mound Bayou, Mississippi today operates health centers at 17 locations in five counties, including free-standing clinics and some schools.

Workers are facing generational challenges like hunger and limited transportation. Cooking classes and vegetables from the community garden. In nearby Leland, a town with a population of less than 4,000, there is one clinic – open even on Saturdays – because many people do not have a car to make the 15-minute highway drive to the nearest small town, Greenville, and no public transportation. Not there .

This type of access to preventive health care is important as area hospitals are cutting back. neonatal services and other specialty care, said Tamica Simmons, chief public affairs officer for Delta Health Center.

“If you’re in the middle of a heart attack, you have to be airlifted to Jackson or Memphis, where they have the equipment to save your life, and so you could die on the way,” she said.

Another key to centers’ ability to improve health disparities is understanding and becoming a part of their communities.

Plaza del Sol is located in the heavily immigrant, mostly Latino neighborhood of Corona, which was New York City, the epicenter of COVID-19 spread. Employees are required to speak Spanish. They regularly visit a local church to host vaccination clinics, numbering in the hundreds. Angelica Flores-DeSilva, the center’s director, said a local principal would call her directly and ask for help in vaccinating children so they would not be denied enrollment.

In Mississippi, staff are trained to recognize signs of abuse, or to recognize that a patient who “fuss and fusses” about filling out a form cannot possibly read. They distribute clothes, food and resources as if they are being given to everyone.

“People hide their circumstances very well,” Simmons said. “They hide illiteracy well, they hide poverty well, and they hide abuse very well. They know exactly what to say.”

To continue serving communities the way they want, center leaders say they are raising as many dollars as they can — but more is needed.

“You can’t be overwhelmed by the problem,” Simmons said. “You just have to take it one day at a time, one patient at a time.”

Associated Press data journalist Kasturi Pananjadi contributed to this report.

The Associated Press Health and Science Department receives support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. AP is solely responsible for all content.

Copyright 2024 The associated Press, All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

[ad_2]

Source link