[ad_1]

Willimantic, Conn. (AP) – The October slaying of a Connecticut nurse making house calls was a nightmare come true for an industry plagued by fears of violence.

Already stressed by staff shortages and increasing caseloads, health care workers are becoming increasingly concerned about the potential for patients to become violent – a scenario that is all too common and on the rise across the country.

Joyce Grayson, a 63-year-old mother of six, went to a halfway house for sex offenders in late October to administer medication to a man with a violent past. She could not come out alive.

Police found her body in the basement and named her patient as the prime suspect in her murder.

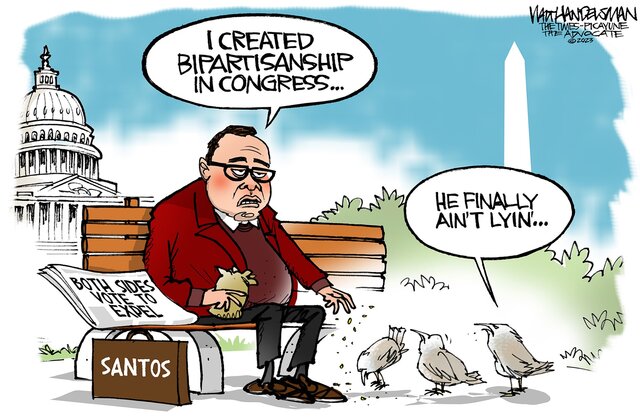

political cartoon

“I used to go to some pretty bad neighborhoods,” said Tracy Wodach, a visiting nurse and chief executive of the Connecticut Association of Healthcare at Home. But, because of budget and staffing issues, that’s no longer an option, she said.

Grayson, who had been a nurse for more than 36 years, including a visiting nurse for the past 10 years, was found dead at the Willimantic Halfway House on October 28. She did not return after visiting patient Michael Reese, a convicted rapist. No charges have yet been filed in the murder.

“All nurses are thinking about it right now, even hospital nurses,” said Connecticut State Senator Martha Marks, a visiting nurse and New London Democrat who is seeking change at both the state and federal level. “Also because they’ve had a lot of close calls.” Law.

Marks said he was once sent to a home and didn’t realize until he talked to clients there that it was a residence for sex offenders. Often, if a nurse asks for a chaperone, the agency will assign the job to another employee who “will not rush,” she said.

Grayson’s death came about 11 months after another visiting nurse, Douglas Brant, was shot and killed during a home visit in Spokane, Washington – a killing that prompted calls for safety reforms, including federal standards to prevent workplace violence. Also invoked.

While murders are rare, nursing industry groups say non-fatal violence against health care workers is not. From 2011 to 2018, the rate of non-fatal violence against health care workers increased by more than 60%, according to the latest analysis from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics.

In fact, according to the bureau, the number of nonfatal injuries from workplace violence involving health care workers has been higher than other industries for years.

In a survey released in late 2022 by National Nurses United, the largest union of registered nurses in the US, 41% of hospital nurses reported a recent increase in incidents of workplace violence, up from 30% in September 2021.

“I knew a home health aide who was punched in the stomach,” said Ha Do Byun, a former visiting nurse and now a nursing professor at the University of Virginia, who studies violence against home health care workers. “Many more nurses were bitten, kicked or slapped by their patients or family members in patients’ homes. Some were attacked by ferocious dogs or abused or made to swear. Notably, the majority of these workers were women.

Byon said specific data on visiting nurses is lacking and he is working on improving the data.

“There’s no way home health workers should be sent into someone’s home or apartment alone,” said U.S. Rep. Joe Courtney, a Democrat who represents the congressional district where Grayson was killed. “You have to have systems and tools in place to minimize the risk.”

Courtney has been pushing for legislation since 2019 that would establish federal regulations that would require health care and social service employers to develop and implement comprehensive workplace violence prevention plans. Industry groups say that although many states require such prevention plans, there is no federal law.

He says the problem highlighted by the Grayson case is not just about safety, but also about attracting and retaining health care workers, many of whom feel the job is too dangerous.

“It’s honestly a huge factor in terms of burnout that employers are so concerned about,” Courtney said.

Marks would like to see laws requiring protective escorts for nurses in some cases, and police to provide caregivers with a regularly updated list of addresses where violent crime has occurred. She also said patients’ charts should be marked to alert nurses about past incidents of violence, if they are registered sex offenders and other information.

According to her family, Grayson was a nurse at the Connecticut Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services for 26 years before serving as a visiting nurse for more than a decade. She was also a beloved foster parent, adopting nearly three dozen children and being awarded the state’s Foster Parent of the Year award in 2017.

What Grayson really knew about Reese and Willimantic’s halfway house is one of many unanswered questions in the case.

His employer, Elara Caring, said that Grayson had Reese’s medical file before he went there, but she declined to say what information was in the file, citing medical privacy laws.

Elara, which provides home care to more than 60,000 patients in 17 states, says it is reviewing its safety protocols and talking to employees about what else is needed. Chairman and Chief Executive Scott Powers said the company’s employees are shocked and mourning Grayson’s death.

The company said it had security measures in place when Grayson was killed. This includes working with states to ensure that patients, including ex-cons, are deemed safe by state officials to receive care in the community and training staff to prepare for such clients. Go. It declined to provide further details about its safety protocols, citing the investigation into Grayson’s death.

Police still have not said how Grayson died, and the medical examiner’s office said autopsy results are pending. Willimantic Police Chief, Paul Hussey, called the murder one of the worst cases he has seen in his 27 years in law enforcement.

Reese, who was on probation after serving more than 14 years in prison for stabbing and sexually assaulting a woman in New Haven in 2006, was taken into police custody while leaving a halfway house the day of Grayson’s murder I went. State records show he was released from prison in late 2020 and twice remanded to custody for violating probation.

Authorities said she had some of Grayson’s belongings, including credit cards, and she was charged with violating probation, theft and using drug paraphernalia. He is being held on $1 million bail. A public defender listed in court records as representing Reese did not respond to an email seeking comment.

Grayson’s family is devastated and is seeking answers to many questions, including whether there were failures of oversight by the state Department of Corrections, state probation officials and the company that runs the halfway house. They also want to know whether Elara Caring adequately protected them, according to their attorney, Kelly Reardon, who said a lawsuit is planned.

“They were extremely concerned that this could have been prevented,” Reardon said. “They certainly felt from the beginning that there were flaws in the system that led to this and they wanted it investigated.”

Collins reported from Hartford, Connecticut.

Copyright 2023 The associated Press, All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.

[ad_2]

Source link